Our communities need residents and leaders to work together collaboratively if we are to solve problems in a way that works for the whole community. This requires courage. This month we highlight sources that can inspire this courage, a story of how the Center had to model the collaboration it teaches, and how to assess readiness to collaborate. ~ Dale Nienow

Finding Courage in the Voices of Ancestors

In our nation’s capitol, the congressional buildings are perched on a hill overlooking various monuments to our great leaders and veterans on the National Mall. It is strange to look at the Capitol buildings knowing that the approval rate for Congress is hovering around 8% while some of our greatest leaders – Washington, Jefferson, Lincoln, FDR, and now King – are sitting outside their windows. We live in a challenging time, one that insists we define yet again how we will live together as a society. Challenging times brought out the greatness of the leaders we memorialize on the Mall. What would they have to say to us today? What speaks to us from their lives?

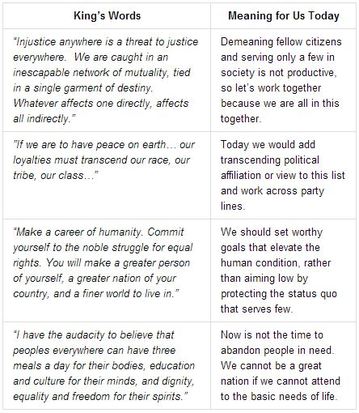

During a recent trip to Washington DC, Dale visited the Martin Luther King, Jr., monument that opened late last fall. Standing near the sculpted figure of King, amidst his many prominent quotes, Dale was invited to a deep level of reflection. “Reading each quote brought up memories of the civil rights movement and also the challenges we have today,” Dale said. "I could hear his booming voice and imagine what his words mean for us today.”

Martin Luther King, Jr., was not an elected official. He was a citizen with a powerful voice who found a way to shape the nation at a key time. He did not seek to alienate others, but invited them to be their highest and best selves. “Darkness cannot drive out darkness, only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate. Only love can do that.”

What if citizens today stepped up with moral courage to create a just and thriving nation? What if we invited each other to work together – to collaborate across our differences – moving toward the light with love?

In our nation’s capitol, the congressional buildings are perched on a hill overlooking various monuments to our great leaders and veterans on the National Mall. It is strange to look at the Capitol buildings knowing that the approval rate for Congress is hovering around 8% while some of our greatest leaders – Washington, Jefferson, Lincoln, FDR, and now King – are sitting outside their windows. We live in a challenging time, one that insists we define yet again how we will live together as a society. Challenging times brought out the greatness of the leaders we memorialize on the Mall. What would they have to say to us today? What speaks to us from their lives?

During a recent trip to Washington DC, Dale visited the Martin Luther King, Jr., monument that opened late last fall. Standing near the sculpted figure of King, amidst his many prominent quotes, Dale was invited to a deep level of reflection. “Reading each quote brought up memories of the civil rights movement and also the challenges we have today,” Dale said. "I could hear his booming voice and imagine what his words mean for us today.”

Martin Luther King, Jr., was not an elected official. He was a citizen with a powerful voice who found a way to shape the nation at a key time. He did not seek to alienate others, but invited them to be their highest and best selves. “Darkness cannot drive out darkness, only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate. Only love can do that.”

What if citizens today stepped up with moral courage to create a just and thriving nation? What if we invited each other to work together – to collaborate across our differences – moving toward the light with love?

Courageous Collaboration

Judgment is easy, collaboration is harder. It is common to critique others and to find justification in our own views. It is natural to take care of our own interests before considering others. It can be instinctual to latch on to initial hurdles and make them insurmountable barriers to partnership. As an agency that teaches collaboration to others, it is often easier to suggest how others can collaborate than it is to model the principles ourselves. At the Center for Ethical Leadership, we have had many occasions where we were tested to see if we would step up with courage to collaborate with others. What do you do when life offers you the choice to collaborate or not?

The Center was invited to apply to coordinate a national community leadership initiative on behalf of a major foundation. This was a significant program involving millions of dollars. The foundation had narrowed the selection to two agencies and invited both to send teams of three people to their headquarters. We assumed they wanted to meet us both in order to make a final choice and we would be directly competing with the other agency. We entered a conference room. On either end of the table were vice-presidents of the foundation. The Center’s team sat directly across from our competitor. We had never met them before, nor did we know their names and roles.

The representatives of the foundation began to describe the initiative, which focused on helping communities work across divisive boundaries to create collective leadership. About thirty minutes into the meeting, the foundation staff asked both teams if we would consider partnering with each other to run the program. We had thirty minutes in an adjoining room to decide. As you can imagine, all the egos, personalities, and institutional self-interests were present in our minds as we talked to each other. Additionally, we had been presented with a three-page list of project tasks with columns to indicate which would be handled by the Center, the partner agency, or jointly held.

After this quick discussion, we decided to give our “shotgun marriage” a go. The first decision we made in our acceptance was to set two conditions – one for ourselves and one for the foundation. For our collaboration, we threw out the list of assigned tasks and agreed that we would both “own 100% of the project.” This started our collaboration with a premise of holding the work collectively – the same work we were going to ask communities around the country to do. The second condition was that the foundation would need to give us four months to build a trusting relationship, blend our ideas, and formulate an approach to carrying out the work.

At one of our relationship-building meetings, the conversation became tense as we described philosophies and approaches. The East Coast approach of research and analysis collided with the West Coast’s focus on the “inner and outer journey of leaders.” One member of the partner organization had enough and said, “You are making me crazy!”

Just when it appeared that we wouldn’t be able to work through this major conflict, another member of their team spoke up. “In my family, my siblings do not always get along,” said Kwesi Rollins. “When people start to criticize each other, we have a saying we use: ‘Be who you is.’” Our conversation immediately deescalated as we realized we had to be true to our own natures and respect the different ideas and approaches of our teammates by not trying to impose our values and ideas onto them.

Ten years later, we are still partners and have expanded our collaboration to include organizations from a dozen states. Kwesi is now a member of the Center’s Board of Trustees. The work in spreading collective community leadership is flourishing, because we had the courage to open up to a different form of collaboration. There were plenty of times when we bumped up against each other, but because we took the time to form deep relationships, we have always been able to come through these times stronger and more capable. What risks are you willing to take to collaborate more deeply with others? What opportunities and possibilities could you cultivate if you held your interests “lightly” and opened up?

To see evidence of this collaboration in action, you can look at the national Community Learning Exchange or contact Dale Nienow.

Judgment is easy, collaboration is harder. It is common to critique others and to find justification in our own views. It is natural to take care of our own interests before considering others. It can be instinctual to latch on to initial hurdles and make them insurmountable barriers to partnership. As an agency that teaches collaboration to others, it is often easier to suggest how others can collaborate than it is to model the principles ourselves. At the Center for Ethical Leadership, we have had many occasions where we were tested to see if we would step up with courage to collaborate with others. What do you do when life offers you the choice to collaborate or not?

The Center was invited to apply to coordinate a national community leadership initiative on behalf of a major foundation. This was a significant program involving millions of dollars. The foundation had narrowed the selection to two agencies and invited both to send teams of three people to their headquarters. We assumed they wanted to meet us both in order to make a final choice and we would be directly competing with the other agency. We entered a conference room. On either end of the table were vice-presidents of the foundation. The Center’s team sat directly across from our competitor. We had never met them before, nor did we know their names and roles.

The representatives of the foundation began to describe the initiative, which focused on helping communities work across divisive boundaries to create collective leadership. About thirty minutes into the meeting, the foundation staff asked both teams if we would consider partnering with each other to run the program. We had thirty minutes in an adjoining room to decide. As you can imagine, all the egos, personalities, and institutional self-interests were present in our minds as we talked to each other. Additionally, we had been presented with a three-page list of project tasks with columns to indicate which would be handled by the Center, the partner agency, or jointly held.

After this quick discussion, we decided to give our “shotgun marriage” a go. The first decision we made in our acceptance was to set two conditions – one for ourselves and one for the foundation. For our collaboration, we threw out the list of assigned tasks and agreed that we would both “own 100% of the project.” This started our collaboration with a premise of holding the work collectively – the same work we were going to ask communities around the country to do. The second condition was that the foundation would need to give us four months to build a trusting relationship, blend our ideas, and formulate an approach to carrying out the work.

At one of our relationship-building meetings, the conversation became tense as we described philosophies and approaches. The East Coast approach of research and analysis collided with the West Coast’s focus on the “inner and outer journey of leaders.” One member of the partner organization had enough and said, “You are making me crazy!”

Just when it appeared that we wouldn’t be able to work through this major conflict, another member of their team spoke up. “In my family, my siblings do not always get along,” said Kwesi Rollins. “When people start to criticize each other, we have a saying we use: ‘Be who you is.’” Our conversation immediately deescalated as we realized we had to be true to our own natures and respect the different ideas and approaches of our teammates by not trying to impose our values and ideas onto them.

Ten years later, we are still partners and have expanded our collaboration to include organizations from a dozen states. Kwesi is now a member of the Center’s Board of Trustees. The work in spreading collective community leadership is flourishing, because we had the courage to open up to a different form of collaboration. There were plenty of times when we bumped up against each other, but because we took the time to form deep relationships, we have always been able to come through these times stronger and more capable. What risks are you willing to take to collaborate more deeply with others? What opportunities and possibilities could you cultivate if you held your interests “lightly” and opened up?

To see evidence of this collaboration in action, you can look at the national Community Learning Exchange or contact Dale Nienow.

Assessing Your Readiness to Collaborate

The Center for Ethical Leadership wrote the book Courageous Collaboration with Gracious Space to help people increase their capacity to collaborate on important issues that move our society forward. When engaging in partnerships with others, one important aspect is to assess your readiness to collaborate. How open are you to sharing leadership with others? To what extent are you willing to share power? How open and willing to be vulnerable are you?

This reflection can encompass both your individual self-assessment and looking at your organization or group. Group leaders can hold their power very tightly, leaving little room for the ideas and initiatives of partners. Individual leaders may cling to their own methods instead of adapting to a partner’s approach. Knowing the degree of openness helps in determining strategies for collaboration.

The Center helps people look for and create pockets of openness. A slight shift in a group or a new idea may invite people to move and think in new ways. Just asking people to assess their openness and readiness for collaboration can cause a shift in how they work with others.

Learn more in Courageous Collaboration with Gracious Space.

The Center for Ethical Leadership wrote the book Courageous Collaboration with Gracious Space to help people increase their capacity to collaborate on important issues that move our society forward. When engaging in partnerships with others, one important aspect is to assess your readiness to collaborate. How open are you to sharing leadership with others? To what extent are you willing to share power? How open and willing to be vulnerable are you?

This reflection can encompass both your individual self-assessment and looking at your organization or group. Group leaders can hold their power very tightly, leaving little room for the ideas and initiatives of partners. Individual leaders may cling to their own methods instead of adapting to a partner’s approach. Knowing the degree of openness helps in determining strategies for collaboration.

The Center helps people look for and create pockets of openness. A slight shift in a group or a new idea may invite people to move and think in new ways. Just asking people to assess their openness and readiness for collaboration can cause a shift in how they work with others.

Learn more in Courageous Collaboration with Gracious Space.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed